Recently, I came across a case of MOSFET burnout, and I'd like to share it with everyone to see what's going on. In a commercially purchased servo motor, both high-side and low-side NMOSFETs in the V-phase half-bridge were found burnt out, while the other two phases showed no issues, and the motor itself was undamaged. One MOSFET had breakdown across all three terminals, while the other only experienced breakdown between the drain and source.

This driver had protections such as over-temperature, over-current, and over-voltage, and the maximum rated current was only half of the MOSFET's ID value. All MOSFETs were surface-mounted on the PCB, and the driver had a metal casing. Under normal circumstances, heat dissipation should not be a problem, and it didn't seem like continuous current heating during motor operation would cause MOSFET damage.

Moreover, even if breakdown occurred due to pulse current, typically only the drain and source would be affected, so why was the gate also affected?

Could it be this?

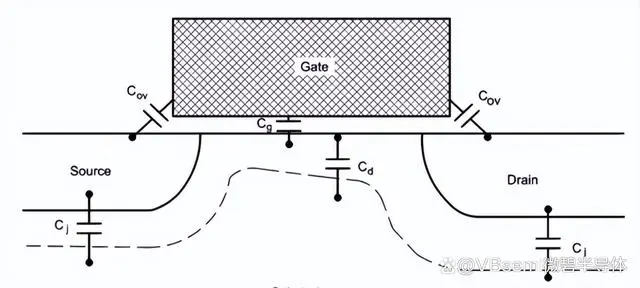

I bet you've guessed it; yes, it's the Miller capacitance. We all know that due to factors such as polysilicon width, channel and trench width, gate oxide layer thickness, and PN junction doping profile, MOSFETs exhibit parasitic capacitance.

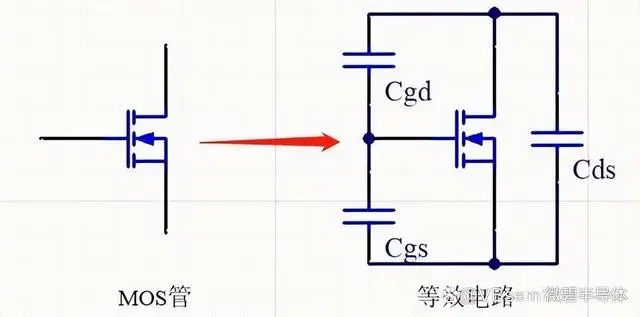

These are the input capacitance Ciss, output capacitance Coss, and reverse transfer capacitance Crss.

Input capacitance Ciss = Cgs + Cgd ;

output capacitance Coss = Cds + Cgd ;

reverse transfer capacitance Crss = Cgd.

From the above equations, we can see that these three parameters are all related to Cgd, which is essentially the Miller capacitance.

These three equivalent capacitances form a series-parallel combination relationship, and they are not independent but influence each other, with one key capacitance being the Miller capacitance Cgd. This capacitance is not constant; it changes rapidly with the voltage between the gate and drain, affecting the charging of both the gate and source capacitance.

When there is a sudden voltage at the drain, such as when the high-side MOSFET suddenly turns on, the voltage at the drain of the low-side MOSFET will suddenly rise. At this point, a current equal to the Miller capacitance multiplied by the rate of voltage change will flow into the Miller capacitance of the low-side MOSFET. When the gate is open-circuited, this current can only charge the gate-source capacitance below, causing the gate voltage to suddenly rise. When it exceeds the gate threshold voltage VTH of the MOSFET, the MOSFET can be easily mis-triggered.

So, we need to protect the gate voltage of the MOSFET to prevent mis-triggering. We can avoid the gate voltage being raised unintentionally by the following methods:

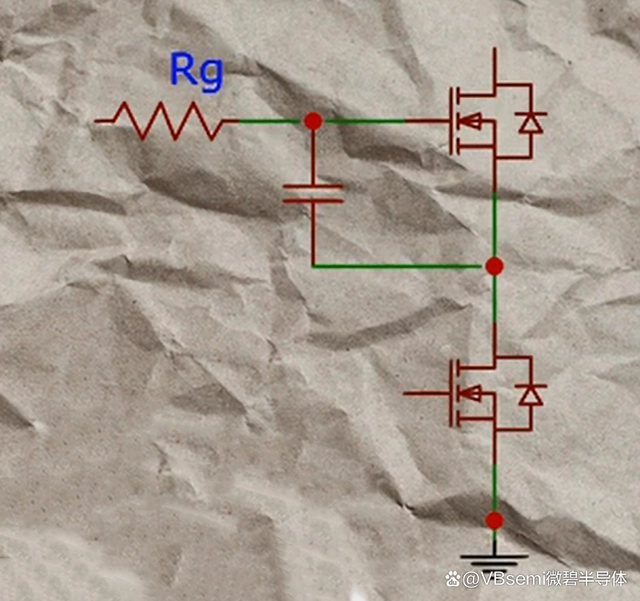

First, we can reduce the current charging the gate capacitance due to the Miller capacitance. Since the Miller capacitance cannot be reduced, we need to reduce the rate of voltage change at the drain. Its role in the half-bridge is to extend the conduction time of the high-side MOSFET. For example, increase the input capacitance by increasing the gate parallel capacitance or increasing the gate input resistance. However, extending the conduction time also means increasing the switching losses, leading to reduced system efficiency.

The second is to strengthen the current cutting path of the Miller capacitance to prevent the gate voltage from being raised above the threshold voltage. A resistor can be connected to the gate to ground. However, this resistor should not be too small; otherwise, a large part of the current will be diverted when the low-side MOSFET is switched on. Especially in drivers with poor driving capabilities, it will lead to a longer turn-on time for the low-side MOSFET, resulting in large switching losses.

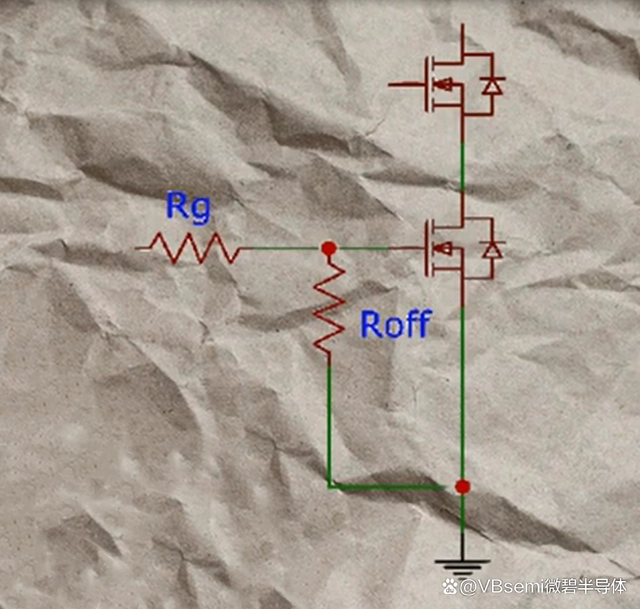

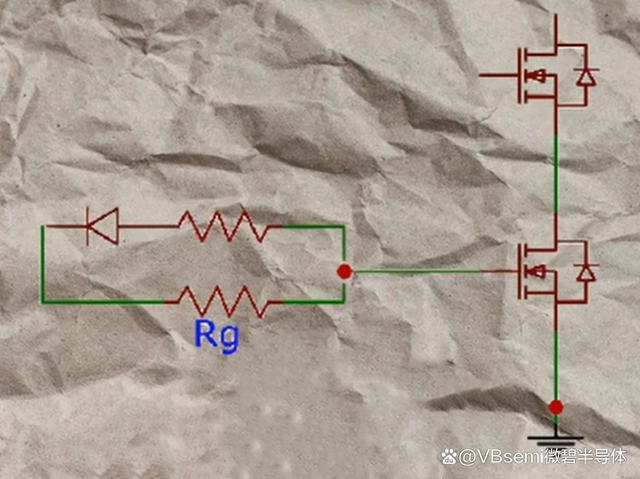

So, there is another solution that only speeds up the discharge but does not affect normal turn-on. For example, add a resistor-diode in parallel to the original current-limiting resistor. In this way, the resistor during normal turn-on is the same as before, but when discharging the Miller capacitance current, this resistor becomes very small and will quickly discharge along the driver's circuit to ground. Moreover, this resistor will also make the normal MOSFET turn-off faster.

However, faster turn-off is not necessarily better. In our actual application, there may be inductance in the wiring from the driver to the MOSFET gate and in the load connected to the MOSFET output, which means fast turn-off implies a sudden change in gate voltage and drain voltage, causing gate voltage oscillation and drain voltage overcharge. Therefore, to speed up the discharge, the value of this additional resistor needs to be determined based on calculations.

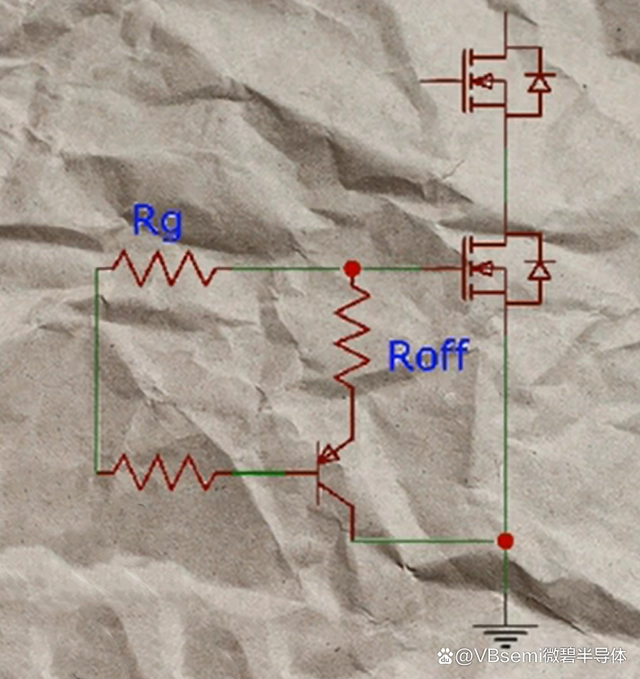

Is there a circuit that is safe and does not increase switching losses without calculation? We can use a transistor and a resistor to form a controllable discharge circuit. Here, the transistor acts as a discharge switch. When the MOSFET driver is turned on, the transistor is cut off, allowing the MOSFET to conduct normally. When the MOSFET is turned off, the transistor conducts, allowing the current to be switched with a smaller resistor to discharge the Miller capacitance.

That's all for this case of MOSFET gate mis-triggering caused by Miller capacitance. I'll share other cases with you next time.

* 如果您需要申请我司样品,请填写表格提交,我们会24小时内回复您